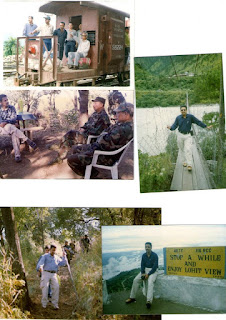

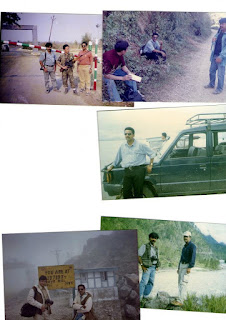

Early today, photographer friend Nilayan Dutta posted on Facebook a long forgotten picture(from November 200) of us in the jungles along the India-Myanmar border to meet a reclusive insurgent leader. That photograph kindled a lot of old memories. Here’s the description of sojourn where the journey itself was an adventure.

Then, looking for some old photographs came across memories of some more unusual journeys in India’s north-east. So sharing them with friends.

Have a GREAT 2013.

WHAT IS LIFE AFTER ALL IF NOT AN ADVENTURE

Circa 2000:

From the moment it was planned, I knew the risks involved.

Reaching the United National Liberation Front guerrillas in Manipur was tough for two reasons.

One, the sheer physical labour involved. Braving intense cold, we had to walk, climb and wade through jungles for two days.

Then, the security forces. Our visit coincided with the UNLF’s 36th foundation day, when government troops were on extra alert to prevent any celebration.

Fortunately, we survived our adventure.

|

| A decade ago in the jungles on the Indo-Myanmar border with UNLF chief Sanayaima, his colleagues and friends Rupachandra and Khelen. Memorable visit. Photographer Nilayan is sitting |

And when we reached the hideout somewhere deep in the forests bordering Burma, we had a pleasant surprise — UNLF chairman R K Meghen.

Better known as Sana Yaima, this is the first time the elusive insurgent leader is coming out in the open.

Make your own way!

The planning was done well in advance, after a lot of homework.

The first approach, through a friend and newsman, was followed up by email.

Nearly a fortnight went for logistics. But by the time I landed in Imphal, Manipur’s capital, everything had been arranged.

Our haversacks full of essentials for the next few days, Photographer Nilayan Dutta and I waited for the morrow with apprehension…

Day 1

YUMNAM Rupachandra, correspondent of The Statesman, arrives with four others — Khelen Thokchom, editor of Sangai Express, a local English daily, two photographers, and an ANI correspondent — at 0600 hours IST. We set off in a Tata Sumo.

An hour reaches us to a small town. After a bit of breakfast, we turn off the highway, onto a dirt track. We arrive at a village and are told to unload our rucksacks and wait.

Ten minutes later, a man in a heavy jacket rides up on a bicycle. He could have been one of the several onlookers gathered around us but for one thing: a small Kenwood two-way radio around his neck.

He is Inga, and chats animatedly with our local friends in Manipuri. Rupachandra translates for our benefit: “An armed posse will escort us from this point.”

Half an hour later, guerrillas arrive. In jungle fatigues, armed with AK-56s, the band of 11 boys, all of them in their early 20s, march into the village in a single file.

The leader, also carrying a radio, is a lance corporal in the UNLF hierarchy. He instructs his boys to pick up our luggage. I gather we are VIPs to them, so we are exempted from carrying our own bags.

With two ‘scouts’ in front, the procession begins. We march in single file. The pace, as it happens in the beginning of any journey on foot, is brisk. Soon we begin to sweat — and off come our sweaters and heavy jackets.

After an hour or so, the water bottles come out. So do biscuits and chocolates. We city-types are beginning to tire and wonder what we have got ourselves into.

On the way, villagers stare at us, as if watching an exotic species. They are used to armed men walking through, but not ‘civilians’ like us.

After two-and-a-half hours, we reach the village where we are to have lunch. All of us lie down on the cool grass. Lunch is rice and dal. It has never tasted so great anywhere before!

CHAIREN is checking the route ahead for enemy movement.

“I am not so much worried about the security forces. What I am concerned about is our rivals attacking unexpectedly,” he says.

Apparently, other groups such as the Issac-Muivah faction of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland — bitter enemies of the UNLF — control some areas en route.

We begin walking again, this time silently. As dusk dissolves into darkness, the fear in my mind accentuates. Everyone is quiet. What if there is an attack? Are these guys capable of warding it off?

The walk continues for the next four hours with little or no banter among us. Around 2000 hours, we reach a riverbank.

Chairen is constantly in touch with his base on radio. We wait. A vehicle is supposed to pick us up here.

After 30 minutes a Shaktiman truck wades through the waist-deep water and comes to our side. We clamber on to the open truck, grateful that we don’t have to walk anymore.

But 10 minutes on, we are all wishing that we had continued walking. The Shaktiman is lurching violently as it cuts through the jungle. Branches hit us from both sides.

My thoughts go back to the Tata Safari ad that says, ‘Make your own way.’ If the makers of Shaktiman could see us now, I think they would just film our journey and use it as promo!

An hour later we reach a village, gorge the simple fare of rice, tinned fish and dal and crash out on the wooden floor of a safe house.

Chairen’s men, showing no signs of exhaustion despite the long day, stand guard. It is cold, but I drop off immediately into an exhausted slumber.

DAY 2

And tonight the password is ‘Topi’

UP at 0530 hours IST. We brush our teeth. After a quick change of clothes, we are off to another house to avoid the prying eyes of the villagers.

A meal is being prepared. All of us go down to the river for our morning ablutions, shivering in the cold. The water is ice-cold but refreshing.

At 0830 hours we have our breakfast of rice and board our “luxury coach”. The Shaktiman is now stacked with hay to make us comfortable!

Within 20 minutes, the semblance of road that existed vanishes. We are now going through a river — through a river, mind you, not by its side.

The driver is least bothered about the pebbles and rocks on the riverbed or the steep inclines that he has to climb at times. All we can do is marvel at his skill and the Shaktiman’s power. The manufacturers have not correctly gauged its capacity, I tell myself.

We halt after six torturous hours. Chairen hands us over to another platoon, led by a tough but smiling corporal, Sajong.

How much longer, we ask.

“Oh, just another hour,” he replies.

He could not have been more wrong in gauging our strength — or the lack of it. It took us three-and-a-half hours to reach our destination.

But I am jumping the gun. Before we begin the steepest climb in our journey, we walk/wade through 22 streams! Our shoes in our hands, the trousers rolled up above the knee, we cross these, wincing every time we put our feet in the bitingly cold water.

At a place called Rest Point, Sajong says it is only a 30-minute climb now. It takes us another two hours.

As we puff our way up the mountain, darkness descends. The track is too narrow. Our legs keep buckling under. My old knee injury starts aching.

Halfway up, Chinglen, staff officer of UNLF headquarters, meets us with steaming coffee and biscuits. The break is welcome.

The guerrillas, for their part, are amused at our plight. For them, climbing is as easy is as falling off to sleep.

AFTER a prolonged break, we arrive on the top. There is a fire burning. The warmth is welcome and so are the moulded plastic chairs. This is a transit camp, explains Chinglen.

Another round of coffee and we start talking. We are shown the hut where we would be sleeping for the next two nights. I look around, trying to soak in the ambience.

A diesel generator is on. Boys, young men and women in jungle fatigues, all armed, are bustling about the hillock. There are several huts scattered around. And guards at all strategic points.

As we apply Iodex to our aching feet, a senior man, flanked by tough-looking guards, walks across to us. He introduces himself as acting chief of staff, UNLF, and welcomes us formally. Then he gives us the biggest news we could have hoped for.

“Our chairman will meet you tomorrow,” he announces without preamble.

Those of us who know how media-shy R K Meghen alias Sana Yaima is are elated. The tough journey suddenly seems worth all the trouble. A legend, who has avoided meeting the media so far, is ready to talk to us. It would be scoop!

A quick dinner and we are all ready for bed. We sleep like logs. Before we drop off, Chinglen gives us the password for the night, just in case any of us ventures out of the hut. It is ‘Topi’.

“Topi, topi,” I mutter as sleep overpowers me.

Day 3

The man they call Sana Yaima

COLD and stiff, we wake up to mugs of hot tea. No sooner is breakfast dispensed with, the man we are all waiting for walks across.

Tall and erect, his gait confident, Sana Yaima, dressed in jungle fatigues and surrounded by armed men, stops in front of us.

“Hello. Welcome to our makeshift camp,” are his first words.

We introduce ourselves and sit around the fire. But for his olive green fatigues, Meghen could easily be mistaken for an academician.

Soft-spoken, erudite and impeccably mannered, he assumed the ancient Meitei name Sana Yaima in his avatar as an insurgent leader. He is far removed from the image of a gun-totting, fiery revolutionary.

Sana Yaima is extremely articulate, his reasoning convincing, his facts solid. A post-graduate in international relations from Calcutta’s Jadavpur University, he had graduated from the Scottish Church College in the same city.

He brings a scholar’s approach to insurgency. Also sophistication. His cadres have the best of weapons and equipment, which include laptop computers.

For a quarter of century, he had shunned the media. Now, after over 36 years of its existence (of which he has been associated for 31 years), the UNLF is ready to let the world know what it is all about.

Sana Yaima’s upbringing and education in the late 1960s in Calcutta, during the run-up to the Naxalite uprising, have had a lasting affect on his outlook. I know that he is liberal, given to respect other ethnic groups and their distinct identities.

No wonder, I say to myself, that he has been leading the UNLF for the past 16 years, first in the capacity of general secretary between 1984 and 1998 and now as chairman. I try to recollect what I know of him.

IF I am not mistaken, he returned to Manipur in the early 1970s and got married.

In 1975, having become an important member of the outfit’s think tank, he went underground. Since then, he has remained in the jungles, away from family, meeting them occasionally in hiding.

Sana Yaima’s wife and two children have taken his absence in their stride. His wife, he is to tell us later, “keeps busy by teaching in a school while both my sons are pursuing higher studies”.

The elder is doing his doctorate in remote sensing application in Manipur University and the younger is in Pune, studying computer science.

Twenty-five years in the jungles have kept the 55-year-old leader fighting fit. For him, this has become a way of life.

Except for making brief forays to Geneva to make a representation on the UNLF’s behalf to the UN Sub-Commission on Indigenous People, and an occasional trip to South-East Asian countries, Sana Yaima has stayed with his 1,000-strong army, which comprises 100-odd women.

And now, after preliminary pleasantries are over, Sana Yaima is saying, “Let’s have the interviews one by one.”

And so it begins.

June 16, 2015 -

Wow…it was a wonderful read. The way you have put it, makes the reader look forward to next paragraph. I was hoping to read the interview too.