and the latest write up.

Nitin Gokhale is Security and Strategic Affairs Editor with India’s leading broadcaster NDTV.

On Saturday, India observed the 50th anniversary of its comprehensive military defeat in the brief border war with China in the winter of 1962. It is important to look back at the events leading to the skirmish before attempting to assess what the future holds for the relationship between the two Asia giants.

In a way, the origins of the border war can be traced to two unrelated events in 1959. In March that year, Tibetan temporal and spiritual leader Dalai Lama fled to India through Arunachal Pradesh (then known as North-East Frontier Agency or NEFA) following a Chinese crackdown in Tibet. New Delhi’s decision to grant the Dalai Lama political asylum did not go down well with China although Beijing did not make its annoyance too obvious.

The second event was India’s discovery of a road, connecting China’s mainland to the restive Sinkiang, built by China through the Indian held but unmanned Aksai Chin area in Ladakh. That discovery triggered the ill-thought ‘Forward Policy’, initiated by India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in consultation with his cousin Lt. Gen BM Kaul, a non-combat officer.

Under that policy the army was ordered to establish posts with less than dozen soldiers in areas that were neither connected by road nor had any strategic value just to show that the land belonged to India. The establishment of these 300-odd ‘penny packets’, as one general later described them, led China to believe that India was preparing for a showdown over the border. Nehru, under pressure from the opposition and the people, was goaded into ordering a reckless plan to ‘evict’ the Chinese from Aksai Chin and NEFA against the professional advice of his military brass.

Under that policy the army was ordered to establish posts with less than dozen soldiers in areas that were neither connected by road nor had any strategic value just to show that the land belonged to India. The establishment of these 300-odd ‘penny packets’, as one general later described them, led China to believe that India was preparing for a showdown over the border. Nehru, under pressure from the opposition and the people, was goaded into ordering a reckless plan to ‘evict’ the Chinese from Aksai Chin and NEFA against the professional advice of his military brass.

Under that policy the army was ordered to establish posts with less than dozen soldiers in areas that were neither connected by road nor had any strategic value just to show that the land belonged to India. The establishment of these 300-odd ‘penny packets’, as one general later described them, led China to believe that India was preparing for a showdown over the border. Nehru, under pressure from the opposition and the people, was goaded into ordering a reckless plan to ‘evict’ the Chinese from Aksai Chin and NEFA against the professional advice of his military brass.

A repeat of 1962 is unlikely but tension between the two countries over the unresolved border issue continues to simmer despite rising bilateral trade ($US73 billion last year).

The intense India-China geopolitical rivalry is playing out in both South and South East Asia. China is making big inroads into India’s neighbourhood by increasing its presence in countries like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar. Beijing’s long-standing relationship with Pakistan continues to be a constant threat to India; the increasing Chinese footprints in the Gilgit-Baltistan province of Pakistan, abutting Ladakh, worries India no end.

The rivalry, in a way, also extends to South East Asia as New Delhi gets sucked into the South China Sea and East China Sea disputes Beijing is involved in. China is wary of India’s rising defence and economic ties with Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan and Australia. But the biggest irritant between New Delhi and Beijing in coming years will be in the form of growing bilateral ties between the United States and India. Strategists in Beijing think Washington is cosying up to New Delhi to balance China’s preeminent position in Asia.

As India looks back at the 1962 border war, its leadership will do well to realise that an increasingly assertive power like China will strive to keep India ‘off-balance’ by what can rightly be described as ‘creeping tactical belligerence’ on all fronts even while it seeks to develop economic and cultural ties with New Delhi.

In the final analysis, New Delhi must learn to look after its own national interests even as it attempts to deal with its increasingly powerful China.

Photos courtesy DRP, Govt of India.

|

With Neten Tashi, a SIB spy in 1962 who escorted

the Dalai Lama from Khinzamane to Bomdilla in 1959 |

|

With my closest friend, travelling companion, fellow journalist

Samudra Gupta Kashyap at the Tawang War Memorial |

|

| Doing a Piece to Camera at Tawang War Memorial |

Tezpur to Tawang–a pictorial journey

|

| Pelting rain greets us |

|

| At Bhalukpong on the border of Assam and Arunachal |

|

| BRO labourers at work |

Jimmy Jesibo, a local activist based in Bhalukpong, a town on the Assam-Arunachal Border is very angry. The reason: the abysmal condition of the road going right upto Tawang and beyond along the China border.

Bearing the brunt of resentment is the hardworking staff of the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), entrusted with widening and improving the roads. Enraged residents, unable to bear the hardship any more, have attacked BRO officials, destroyed their vehicles and have thrown heavy tippers and bulldozers down the steep valleys in the past six months.

Half a century earlier, this was where the marauding Chinese routed the Indian army, pushed into a war it was not prepared for in a tough terrain it was not used to.

Today the soldiers are definitely better looked after and unlike in 1962, they are well-trained to fight in the high-altitude terrain of Arunachal Pradesh.

But five decades down the line, infrastructure, especially the main arterial road connecting Tawang to the rest of India remains a major worry.

Jimmy Jibeso says, “Since the 1962 war, this route is very important for the north-east due to the Indo-china border. If the condition of the road is bad then how will Bofors reach the border in case of an attack. What will we do then? One needs good and big roads for Bofors. This is our main concern. Second concern is that medical help is not good up in Tawang and other places. If a patient has to be taken to Tezpur, Guwahati and other places, the road is so jerky and bad that the patient dies on the way. So we want good roads.”

The Army, more than anyone else really requires this axis to be an all-weather road. Since 2010, it has inducted a full new division – over 20,000 additional soldier -for this sector.

|

| Deteriorating roads |

|

| The majestic Kameng |

The Border Roads Organisation, a quasi-military organization is entrusted with building and maintaining these strategic roads. Come rain or winter, labourers of Border Roads Organisation work to keep the only road link to Tawang open through the year but at the moment they are fighting a losing battle. The fault lies not with them but with people higher up who planned the widening of the only road without building an alternative.

Constant landslips, frequent blockades are a recurring challenge. But landslides apart , BRO officials tell us that they are plagued by a shortage of labour in this sector. Earlier, large groups from Jharkhand and Bihar made their way to these parts. No longer, since now plenty of work is available in their home states. Excruciatingly slow environmental clearances both by the central and state governments add to the delays.

|

| Many such waterfalls by the road. Koyla was not shot here though |

|

| Landslides are a common phenomenon |

|

| Once a journo, always a journo! |

|

| A BRO labourer |

|

| For most of the 300 km, the road is as rough as this |

|

| My colleague Nirmal hard at work |

|

| One of the lesser known war memorials |

|

| Clouds just before Sela |

|

| Sela behind me |

|

| At Sela–13700 feet |

|

| The lake after Sela |

|

| The War Memorial at Tawang |

|

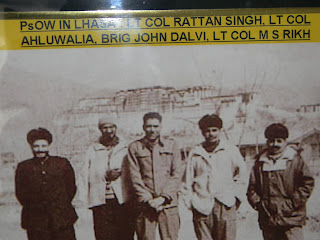

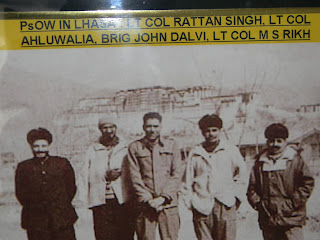

| Archival pix at the War Memorial. Indian PsOW |

|

| A Monpa man |

|

| A young monk taking a break in the Tawang Monastery |

|

| School children at Jang |

|

| At Jaswantgarh–the most famous War Memorial in this sector |

|

| No matter what the condition of the road, Army vehicles continue to ply |

|

| Unusual site: BRO labourers taking a chess break! |

|

| Terribly slushy road |

|

| The difficult road |

|

| At the Sela zig-zag–doing a piece to camera |

|

| Chinese agression in 1962. Captured in a photo |

|

| The Buddha statue inside Tawang monastery |