Nearly 30 months after the border standoff at Dolam (popularly known as Doklam) was resolved, China is far from giving up attempts to whittle down India’s influence over Bhutan, the third and most important angle of the triangular mess in the strategically important Himalayan frontier.

Throughout 2019, Beijing sought to increase the pressure on the Kingdom of Bhutan to arrive at a settlement over the still unresolved China-Bhutan border at the earliest. Feelers were sent and subtle hints dropped at every conceivable opportunity—be it at the UN or during trips by Chinese officials to Bhutan. Among the visitors was then Chinese envoy to India Luo Zhaohui since Beijing does not have an envoy in Thimphu as the two countries do not have formal diplomatic relations. So far, Thimphu has stood firm, helped considerably by India’s consistent and unambiguous support in looking after its security interests. The Indian Army continues to work in tandem with the Royal Bhutan Army in the Chumbi Valley—the scene of the 72-day faceoff in August 2017—while diplomats and senior security managers maintain close and frequent contacts with the decision-makers in the Kingdom.

Early this month, India’s newly appointed Army Chief Gen. MM Naravane, outgoing Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale and Samant Kumar Goyal, the head of India’s external intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), together made a quiet trip to Thimphu to confer with present king Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck and his father, the fourth king Jigme Singye Wangchuck, on matters that require immediate attention as India and Bhutan try to find a new idiom in their robust relationship. The border situation is always on top of the agenda when such discussions take place although of late a fresh irritant has crept into the relationship: the question of charging a fee—albeit a fraction charged to non-Indians—to Indian tourists visiting Bhutan has created a bit of resentment among tour operators and tourists.

On top of the list in the discussion on border was, of course, the vexed boundary question between China and Bhutan and the many ways in which it affects the security of India’s strategically located Chicken’s Neck corridor connecting the north-east with rest of the country. India, aware of the pressure on Bhutan, has stepped up its engagement on the issue at the highest level. In New Delhi’s assessment, sooner or later Thimphu will have to restart boundary talks with China and undertake some give and take. Having accepted the inevitability of such a possibility, India wants to ensure that its territorial integrity in the area is not threatened. New Delhi, therefore, ensures that all the relevant stakeholders in the national security set up are in constant touch with the Bhutanese leadership at the highest level.

The dynamics in the India-Bhutan relationship have particularly changed since the 2017 Dolam border crisis which starkly demonstrated the vulnerability of the tri-junction of India, China and Bhutan from the point of view of India’s security concerns.

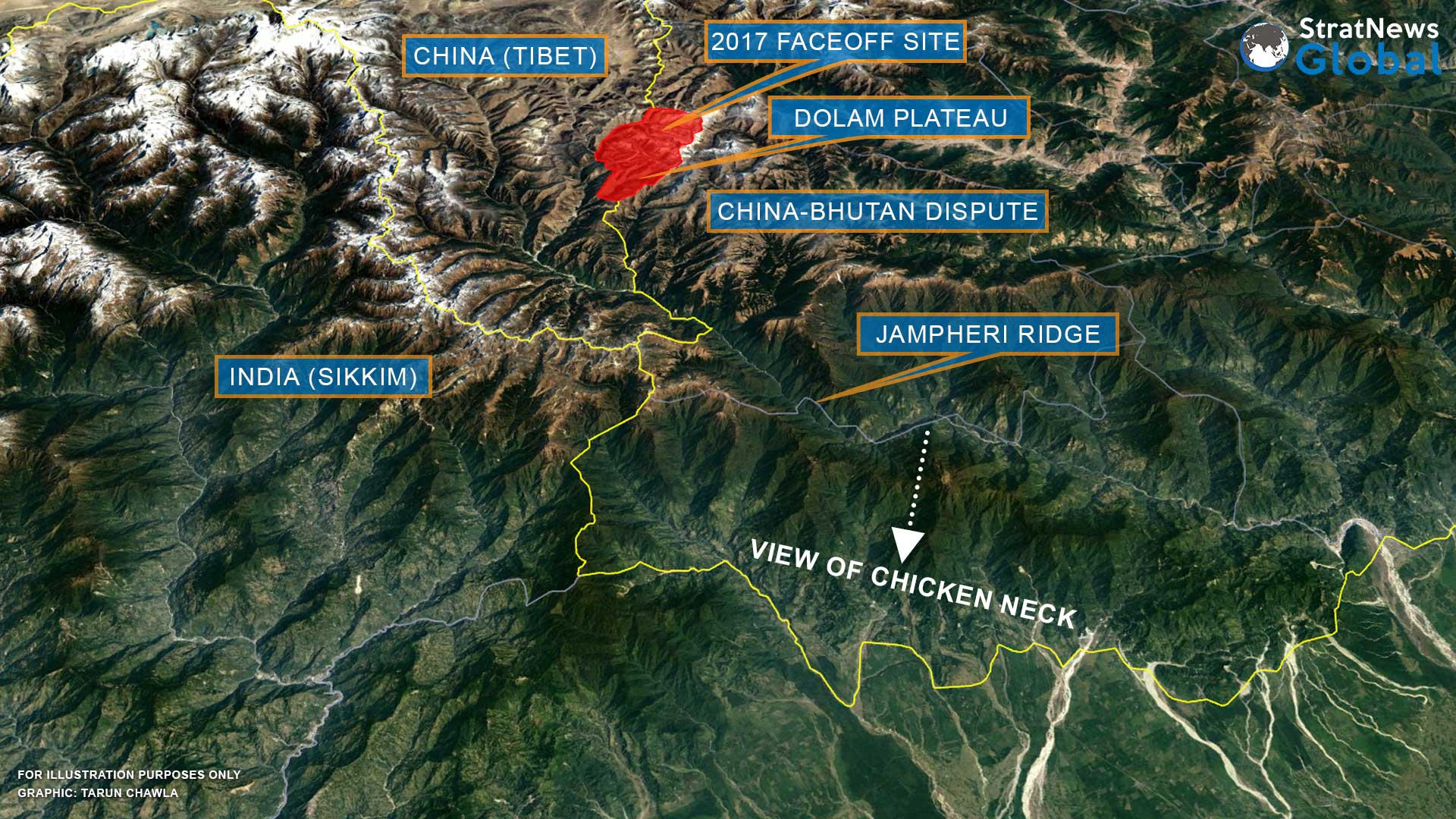

That time, the Indian leadership handled the standoff deftly and forced China to back off from its attempt to extend a dirt track up to the Dolam plateau which looks down India’s Siliguri corridor. In 2017, India could swiftly intervene by stopping advancing Chinese construction team coming from the western side of the Dolam plateau because Indian Army posts located on the west of the plateau can closely watch Chinese movements and act swiftly. More than two years after that crisis, India has strengthened its already formidable presence on the border and has stepped up its coordinated patrols with the troops of the Royal Bhutan Army along both sides of the Dolam plateau.

However, India and Bhutan will have to make sure that any potential border settlement between Thimphu and Beijing in the future ensures that the Dolam plateau is not accessible to the Chinese troops either from the western side (attempted in 2017) or from the eastern side by skirting around the Ami Chu (river)—a track that is away from the prying Indian eyes, climbing the Jampheri ridge and reaching atop the Dolam plateau (see map)—making all Indian defences in the area infructuous since access to Dolam can give a virtual free run to any force wanting to roll down to the Siliguri corridor. Others disagree. Veteran military officers who have served in the area point out that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will have to deploy a large body of troops to break through strong Indian defences. Any advancing Chinese force will have no artillery cover or logistics support to sustain it beyond a couple of days.

Militarily, India can handle any crisis. What New Delhi needs to worry about is the increasing unease among the Bhutanese about being a pawn in the geostrategic game of chess between two big powers—India and China. More than 15 years of controlled democracy (despite an elected Parliament and a cabinet, the Monarchy still has total control over the Kingdom’s security and foreign policies) has given Bhutanese people freedom to question some of the traditional assumptions about the India-Bhutan relationship. Many Bhutanese wonder if the country should continue to depend upon India to guarantee its security or it should see the writing on the wall and settle the boundary question with China independently. The King, as pointed out, so far has absolute say in how Bhutan should deal with India and China but with democracy gradually taking roots in the country, the monarchy will have to take into consideration people’s opinion in the years to come. Keeping in view this possibility, New Delhi and Thimphu are constantly engaged in dialogue at the highest level. The recent trip by three important security managers was in keeping with this thought process, sources pointed out. What eventually happens will depend on many factors in the future but there is no doubt that away from public glare a fascinating geostrategic contest is taking place at India’s doorstep.